Reading Vonnegut in the playroom

Visiting the grandkids is always a special treat and we make the day-long drive as often as we can. As the years roll on, our visits change from participating in the routines of one baby to playing with the toddler she becomes and then sharing our attention with another baby.

Now they are six and three, two active little girls. They greet us with big smiles and warm hugs. A guided tour of their rooms usually follows, and we are gradually folded into the fabric of their daily lives. The fabric grows with strands of chaotic dinners, well-practiced morning routines that get them off to school on time, games of hide-n-seek, periods of calm where they play alone or, more recently, together, and special moments with Grandma or PopPop playing a game or doing an art project.

Our six-year-old is taking to the squiggle game, that old classic familiar to psychologists, especially those who work with kids. We take turns going first, drawing a squiggly line for the other player to turn into anything they can imagine.

“PopPop,” she says, exasperated, “you always draw people.”

“Oh, so I do,” Dawn breaks on Marble Head, and I resolve to add more variety to my drawings. Meanwhile, my partner is busy turning my squiggles into things like a butterfly carrying a crown to a castle, a mermaid swimming next to her house beneath the sea, a hand reaching up from the couch to grab a tissue sticking out of its box. She is a fountain of ideas cascading from the faucet of her active imagination and last week’s cold.

When big sister is done with our squiggle game, she turns to Grandma who just taught her something new on this visit. You start with a grid made up of rows of dots filling a sheet of blank paper and take turns connecting two dots at a time with a straight line. The object of the game is to connect four dots to make a square and to make more of them than your opponent. When you finish one, you claim your territory by writing the first letter of your name in the box. Big sister has a knack for this contest, and Grandma doesn’t have to give her any advantages to be sure she wins.

Little sister sits with us and colors or practices writing her name with Grandma. When she’s had enough of that, she plays with her dolls. She dresses them, feeds them, and combs their hair, talking to them all the while in a quiet voice meant only for their ears.

One morning, the girls surprise us by putting on a dance performance complete with music, princess dresses, and dancing partners from the ranks of their teddy bears. We sit where they tell us, an appreciative audience captivated by their artistry and grateful to be a part of the production.

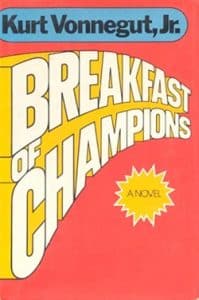

Later in the day, they retreat to little sister’s bedroom with Grandma for some serious doll play, and I take the opportunity to have some private time in the vacant playroom. I grab a book from the grown-up’s shelf, Kurt Vonnegut’s “Breakfast of Champions,” and start to read. In the opening chapter, I meet the principal characters, Kilgore Trout, a science fiction writer whose strange ideas, we are told by the author, will drive one particular reader, Dwayne Hoover, mad.

It is not that Trout is trying to make people mentally ill, but Hoover happens to be especially vulnerable because of the “bad chemicals” in his brain. Vonnegut tells us that mental illness is caused by a combination of bad chemicals scrambling the brain and creating fertile soil where bad ideas can grow.

I had read this book decades ago, but now with the perspective that comes with age, the opening chapter is new to me, and I see it as a prescient description of the cause of mental illness. The book is much more than that, and the details elude me, but Vonnegut’s critique of our culture is there in the beginning with his jabs at war, greed, and consumerism.

Early in the story, the narrator tells us that the bad idea that Dwayne Hoover took from one of Trout’s books is the idea that Hoover alone has free will in a world where everyone else is a programmed robot. Where this kind of thinking can lead is the rest of the tale, but I don’t get very far before Grandma and the kids return with an announcement. They have prepared a gymnastics show, and I am to be the audience and photographer.

I put down Vonnegut, Trout, and Hoover and pick up my camera. Our six-year-old turns on some music, and the girls do some amazing acrobatics with their doll or teddy bear partners. For a brief beautiful time, I forget about the culture that Vonnegut criticized for the very same flaws that plague us today.

All around us wars continue to rage, greed oils the machinery of business, and government, and consumerism has become the norm. But here, in the play of two little girls, something different is happening. It is the outpouring of creativity and joy that brings me back to the inscription on Kilgore Trout’s gravestone. “We are healthy only to the extent our ideas are humane.”

And so I wish very hard that this place and every place where children play may be an incubator of humane ideas and a source of enduring health.